The traits of true engineering culture

Taking a walk

End of last Month I took a walk, literally. I’ve walked from the outskirts of Porto to Santiago de Compostela as part of the Camino Portuguese. For me it was a walk of just about 200 kilometers that brings you across the Via Romana XIX (the old Roman road) to Santiago.

The nice thing about walking on average about 25 kilometer a day is that it’s a simple life, that most importantly allows you to clear your mind. The daily routine is like this: “wake up at around 6:00AM, gather your belongings in a backpack, put on sunscreen, check if you’re wearing appropriate attire for the start of the day, check to see if you have enough water, put on your socks and shoes, pick up the backpack and go!”. That’s it, walk until you think you’ve done enough, check-in to an auberge and chill out + repeat. All while enjoying the scenery you pass through and of course have a taste of the local food and drinks, and all the conversations with others on the pilgrimage. A lovely way to break out of the daily office life, I can highly recommend.

Engineering culture

The quietness so to speak and getting away allowed me to gain a different perspective on a tough subject matter that has been on my mind for at least a couple of Months now, possibly even longer. The days walking allowed my mind to wander and have uninterrupted attention. That has been scarce with all the things going on in daily work-life at the moment. I was surprised that somewhere after a couple of days an idea dawned on me. It’s not so much that all the sudden I found enormous clarity on the subject, but rather my curiosity was sparked to look further into the subject. The subject of engineering culture and especially how that may help companies become more productive.

Skunk Works

I had already seen a few articles and documentaries on the legendary Lockheed Martin Skunk Works and their founding engineer Kelly Johnson. The specialist unit of the aircraft company which has produced some amazing aircraft has a rich history in being able to produce amazing aircraft like the SR-71 Black Bird, in seemingly impossible timelines. How did they manage to do this? There’s a great overview on the Skunk Works site on Kelly Johnsons 14 rules which serves as the operating model.

Inside story

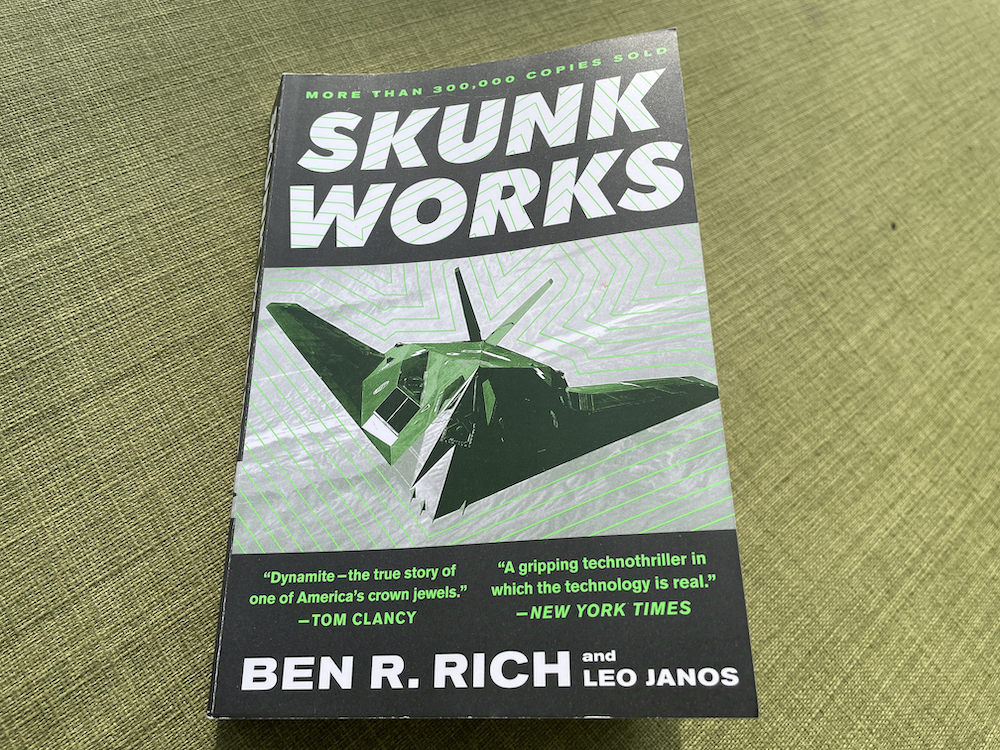

Parked on my reading list I had the book called “Skunk Works” by Ben R. Rich, a former employee engineer at Skunk Works that later became the executive to replace Kelly Johnson. Last week I finally got around to reading it. His story gives a lot more insight into how those 14 rules were applied and how they (as much as possible) keeps the company staying productive at high pace.

Different ways to lead

What I thought was remarkable about the book is that Ben Rich is a completely different type of leader than Kelly Johnson was. Ben Rich is the type that say: “I’ll get out of the way and let the smart people do what they need to do”, no micro management, no second-guessing. This creates an environment of high-trust and relative harmony by empowering the people that need to make decisions. It also allows a company to scale it’s engineering. On the other hand Kelly Johnson was way more involved in the tiniest of detailed design decisions. Johnson also appeared to be very direct, bullish, immovable in his opinions (supported by the fact he was right on many occasions) and hyper-aware of all aspects of the business. A unique skill/trait for founders that will help drive early success and gaining momentum. I guess they both stepped in at the right time for their leadership skills and traits to pay off and earn their successes in their own ways.

Bureaucracy kills innovation

Blatantly obvious, but in the book supported with a factual account is the fact that adding “jobs to complete” that are non-value-adding to a list of work to-be-done introduces enormous delays (or shall we say “additional time-to-value”). The significant impact of this only becomes clear after you compare timelines with-and-without the overhead. The book explains one of these cases where the timeline of building an aircraft and the number people involved literally doubles, if only to account for the audits and red-tape added onto a project. That’s crazy!

This goes to show how bureaucracy kills innovation. In the mind of the engineers, design could have been pushed way further by spending that time engineering instead of gathering sign-ofs. This is where a hefty price is paid in progress as well, because not only are people pulled out of their creative flow, but also they have to replace that flow with performing boring, mind-numbing jobs like filling out paperwork (multiple times), meetings, and more meetings, etc. which is not utilizing their brain capacity in an optimal way. Besides the overhead, the disruption also comes at another price. Having to get back into the flow is often difficult and thus brings a risk of adding further delays. Design is not a seamlessly resumable activity.

Rule #3, minimize the number of people related to the project

Kelly Johnsons’ Rule #3 is also what comes into play. Leaders can push back on bureaucracy that is pushed upon them by clients/customers. By pushing back, they can scrutinize the number of people involved in the completion of work and aim for a lean setup. The less people involved, the less hand-overs, the less cross team communication is required, minimizing the overhead and maximizing the productive time.

Small

The notion of minimizing the number of people involved also builds on another idea, the idea of building in the small, limit the number of people working on large shared responsibilities and maximize their decision making powers. So, basically like Ben Rich did at Skunk Works, “to get out of the way”. That gesture came with one important dependency, and that is “whenever the sh#t hit’s the fan, I’m the first one you inform without delay”. Providing a means for creating accountability and transparency on things that matter.

Software engineering

We’ve been talking about aircraft engineering and in my opinion this also applies to software engineering (and possibly many other engineering practices) where in short time frames stuff needs to get delivered. The ““secret”” so to speak is in minimizing distance between designing and creating. By pushing for zero-distance feedback loops, deviations can be noticed and corrected at the earliest. This saves rework and maintains context. Thereby the engineer doesn’t need to circle back but can remain the thread of thought and continue.

Compliance capital

The other key idea is of course maximizing the value-added work by removing unnecessary distractions. Distractions in the form of overhead. We know from safety science and the writings of professor Sidney Dekker that a lot of the added overhead doesn’t make things more safe at all, it just documents that something is done according to spec and procedure. Working with governments and large institutions will always involve some form of additional overhead, but the aim is to push back as hard as we can on that to minimize the negative impact.

Build your own Skunk Works

A few companies have tried and succeeded in building their own Skunk Works division. Most notably the creation of the Ford Mustang in the early 90’s by the Ford Special Vehicle Team (SVT) is a prime example of how even big companies can create an environment in which engineering thrives and there is a lot of autonomy for these units to operate. So it can be done and just that is inspiring!

Sustaining success

There is a massive amount of regulation and bureaucracy created by governments and institutions each year and pushed towards organizations with the demand to comply. The key for companies to sustain their pace is to do the minimum possible to demonstrate compliance and adopt lightweight interpretations of the rules and regulations where they can. This therefore depends on leadership at these companies to minimize the impact of these burdens and find ways to push back or minimize scrutiny where possible. This is a bit in contrast by the nature of auditing, which relies heavily on evidence creation and documenting the process of the process. Over time many organizations succumb to the regulatory pressures, it’s just too much. But that may also provide an incentive to build your own fresh Skunk Works division and carve out a piece of the organization that can operate under relieved constraints. Rinse and repeat.

Engineering culture is EVERYWHERE

Let’s end on a positive note. Within these large companies engineers and their engineering spirit is everywhere. We just don’t get to see it as often as it could/should be demonstrated/shown. The reason is more than often found in stifling bureaucracy, which in the long term creates indifference and mediocrity. It’s my opinion that “if we enable them, they will deliver”. This will require suitable leadership and in many cases a long uphill battle for orgs that are stuck with a large compliance burden. Happy to help you all push back!